Dreamlogs is an interdisciplinary project that aims to map the “landscape of associations of ideas” on the Web. It was reactivated at the Institute for Advanced Studies of Aix-Marseille University (Imera) in 2022/23, in a new context where LLMs such as ChatGPT, combined with a paradigm shift in neuroscience, challenge the post-truth era.

This paradigm shift, with theories such as “Predictive Coding” and the “Free Energy Principle”, opens the way to the use of new conceptual tools such as “Free Energy Landscape”. These tools could make it possible to achieve what Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays, author of the (in)famous book Propaganda, would never have imagined in his worst nightmares: a topography of the “unconscious of capitalism” (cf. my project The Google Adwords Happening, about the advent of “semantic capitalism”).

The following text, written after my residency at the IAS, begins with the description of an artistic Web project and its prototype, then crosses questions of constrained literature, graph theory, neural networks, psychoanalysis, neuroscience, theoretical physics, topos theory, theoretical computer science, topological data analysis, etc. I leave it to the specialist readers to point out possible inaccuracies. For my part, I try to build bridges, sometimes quite crumbly, between these different fields, which aim to explore improbable and hidden paths in the jungle between aesthetics and politics. Regarding past exhibitions, articles on this work, and credits, see Appendix 1.

A topography of the “unconscious of capitalism”?

“The total number of minds in the universe is one.”

Erwin Schrödinger

The prototype, created in 2003 in the form of a Google hack, proposed a new way of browsing the Web, close to free association or dreams: the user chooses a word (or a syntagm, i.e., part of sentence) and the interface displays its “semantic neighborhood”, that is to say the set of all web pages that contain it. In this neighborhood, we select a second syntagm and we repeat the operation. The route is recorded in the form of a Dreamlog. The ambition of this system of real-time Archeology of Knowledge was to reveal, beyond the utilitarian dimension, the topography of this hidden reticular semiotic space. If you are familiar with Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models, that are trained on massive amounts of texts to predict the next word given a series of initial words, you may already get the relation between Dreamlogs, words embeddings and LLMs. The associations of ideas in Dreamlogs are more or less probable depending on how often the chosen syntagms are appearing together in the same webpages.

Homepage of Dreamlogs in 2006 (retrieved from Archive.org)

Example of an intermediate page from Dreamlogs (retrieved from Archive.org)

Partial view of a Dreamlog (2005 / user “Pold”) which started from the syntagm

“Dangerous work” to arrive at the syntagm “Interface” (retrieved from Archive.org)

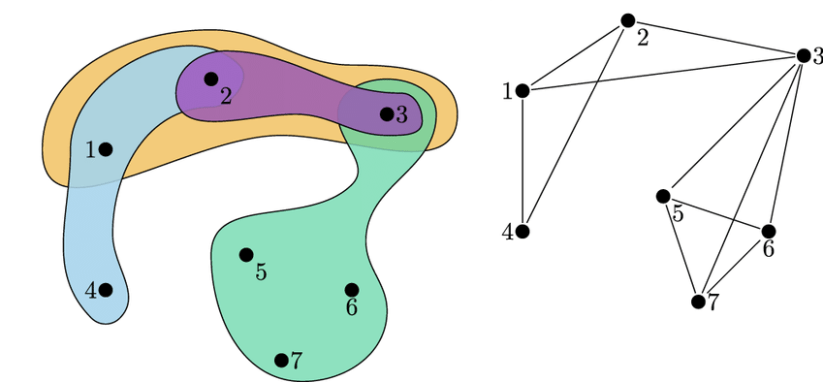

The concept of hypergraph underlies the initial intuition of the project. This notion was developed in the 1960s by the mathematician Claude Berge, founding member of Oulipo, a French literary movement to which Dreamlogs refer (in Appendix 2, you will find more information about the genesis of the project in relation to Oulipo and the work of Georges Perec and Marcel Bénabou).

Hypergraph (right) associated with a graph (left).

Here, nodes represent syntagms (words or phrase fragments), and hyperlinks represent web pages.

E.g. the hyperlink (1,2,4) represents a web page containing the words 1, 2, and 4.

It is natural to associate the improbable trajectories of Dreamlogs with “primary processes” that Freud described, the very ones that govern dreams and free association. In contrast, “secondary processes” correspond to the utilitarian narrative order, responding to a functional logic, often described as “rational,” reflective, and normative. In the context of an LLM, one can loosely evoke primary-process-like wandering by using a higher sampling temperature (more on this loose correspondence later). Temperature can be adjusted via the OpenAI API; higher values amplify unpredictability and can make texts feel less constrained by dominant norms—less “polite” or politically correct in a conformist context—yielding more improbable and imaginative continuations (this often feels more free-associative or surprising, though tone and “politeness” primarily depend on alignment and decoding choices rather than temperature alone).

I have tested that ChatGPT-4 allows you to simulate the behavior of Dreamlogs, while adjusting the temperature so that the associations of ideas are more or less improbable. This experiment gives a direction to follow in the perspective of a future reactivation of the project. Details of one of these simulations are presented in Appendix 3.

My project Dadameter (2007), an attempt to map language on a large scale, is an important step in my research around Dreamlogs (the Dadameter refers to the French writer Raymond Roussel and his influence towards Dada, Duchamp, surrealism, Nouveau Roman and Oulipo). Developed with the help of computer scientist and AI specialist Valeriu Lacatusu, it uses a semantic distance called Google Similarity Distance, based on the notion of lexical collocation: two words are considered close if they appear together in a large number of web pages. This distance is inversely proportional to the correlation, or the probability of transition from one word to another, concepts that are found in modern LLMs, which, thanks to techniques such as words embeddings, identify patterns in a vector space where distances and orientations reflect semantic relationships (note that modern embeddings learn distributed semantics via predictive objectives and context windows, capturing polysemy and long-range structure more robustly than plain co-occurrence counts).

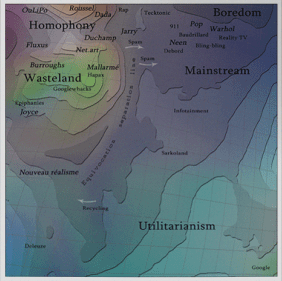

On the Dadameter map below, the primary processes are mainly located near the green zone called “Wasteland”, where the probability of transition from one word to another is minimal, reflecting a low correlation. Conversely, around the zone of “Mainstream”, speech is more predictable.

There is no widely accepted theory that describes the behavior of such linguistic phenomena, although models exist. However, at this point, to take a step forward, it is interesting to discuss some concepts of thermodynamics and information theory, as I do in the next section. I leave for future updates of this text the explanation of the reasons why I consider the Dadameter map as a first hint towards a topography of the “unconscious of capitalism“.

Left: the Dadameter map

Free energy

In the context of information theory, internal energy and entropy may be interpreted in terms of the transition probabilities from a word i to a word j, which we denote by p(i→j). What follows is a toy model that repurposes thermodynamic terms to express two opposing pressures in language—surprise versus diversity. There is no claim of physical temperature or unit-consistent thermodynamics here. We can, as a first approach, define the internal energy U(i→j) as the opposite of the log-probability of transition from a given word to another, − log(p(i→j) ). High internal energy indicates low transition probability, while low internal energy indicates high transition probability. Internal energy measures the surprise of the event (a.k.a self-information of the transition; a modeling convenience rather than a physical energy). Common words correspond to low-energy, stable, low-surprise states, whereas rare words correspond to high-energy, unstable, high-surprise states.

The Shannon entropy of a word i is classically defined as: S(i)=−∑ j p(i→j)log(p(i→j)). A high entropy for a given word would mean that that word can be followed by a wide variety of other words with approximately equal probabilities, while a low entropy would indicate that the word is usually followed by a small set of specific words. Entropy thus measures the diversity or uncertainty of the contexts in which a word appears. A high value of S indicates that the word is used in a wide variety of contexts, while a low value indicates more specific usage. On the Dadameter map, this would correspond to the criterion Polysemy vs. Univocation.

Each state of the semantic graph will thus have a certain “free energy” which will receive a negative contribution from entropy, i.e. F = U – T x S, where T is defined as the analog of a temperature. Throughout, U – TS serves only as a mnemonic balance between surprise and diversity—a metaphorical objective, not the variational free energy used in neuroscience.in this toy model ; also, we put aside the questions of normalization between both terms of the free energy. Intuitively, the “- T x S” part means that some heterogeneity in the medium may trigger some change of state that will lead towards homogeneity: a high free energy state, or low entropy, will transform into a lower free energy state, with an entropy increase by analogy with the second law of thermodynamics (this is a metaphorical mapping, not a physical claim). Temperature plays a modulating role between U and S. At higher “temperatures,” the system becomes more exploratory: randomness increases, associations grow more diverse, and the discourse drifts through less probable paths. In this toy analogy, this reflects a move toward greater entropy and variety in the sampled trajectories, not toward thermodynamic stability.

In the context of the Dadameter, we can simulate possible configurations for the free energy on the axes Mainstream-Wasteland on the one hand and Univocation-Polysemy on the other hand. The first axis starts from a situation where the internal energy is low, i.e., transition probabilities are high, and the temperature is low (Mainstream) to a situation where the internal energy is high, i.e., transition probabilities are low, and the temperature is high (Wasteland). The second axis goes from a low entropy (Univocation) towards high entropy (Polysemy). We observe different possible types of relief:

In the first case, a ridge line separates the extreme regions of the Mainstream and of the Wasteland, while in the second, the two communicate (we can imagine fluctuations from one case to another over time).

This very rudimentary toy model allows us to imagine a third dimension to the Dadameter map. The intuition is that this topography could be a partial and “compressed” view of the landscape I seek to visualize, “dimensional reduction” of an ever-changing hypergraph, where associative flows slide towards more stable states, at the bottom of the valleys. Free energy represents the potential gap that information has to cross, starting from a low entropy state, with higher free energy, before returning to a more probable and stable configuration.

In the definition of free energy as F=U−TS, the energy U represents the misalignment with the system’s expectations, and the entropy S is the system’s diversity and uncertainty. Minimizing free energy involves balancing these terms.

- In low-temperature regimes of this toy model, the system prioritizes reducing U, achieving stability and coherence, even if entropy S decreases. This creates a structured, predictable state with minimized surprises. This is usually denoted as “exploitation mode.”

- In high-temperature regimes of this toy model, entropy S plays a larger role, encouraging diversity and “exploration mode.” This allows the system to embrace uncertainty and novelty, which can temporarily increase U but still minimizes F through a higher contribution from TS.

In this toy model, the interplay between U and TS governs whether the system favors exploitation (stability, lower entropy) or exploration (novelty, higher entropy).

If we consider the cultural history layer, we can metaphorically view it as a dynamical system that balances two pressures—surprise/misalignment (U) and diversity/novelty (S)—in the spirit of a free-energy-style trade-off: F=U−TS, where U represents the misalignment of cultural practices with established norms, S is the diversity and novelty of ideas, and T reflects the system’s openness to exploration.

- During exploitation-heavy periods, such as Academic Art or Neoclassicism, the system reduces U by stabilizing cultural norms. This decreases entropy S, creating a structured and predictable state. Free energy remains low because the reduction in U outweighs the loss in TS.

- In exploration-heavy periods, like Dadaism or Surrealism, the system embraces uncertainty and diversity, increasing S and allowing for novel ideas. In high-T regimes, the contribution of TS to free energy minimization dominates, even if U temporarily increases due to misalignment with norms.

This balance between U and TS drives the oscillations between stability and innovation that characterize cultural evolution.

Of course, this toy model doesn’t capture the full Free Energy Principle, which actually deals with a form of variational free energy. I encourage you to listen to this Mindscape podcast by Sean Carroll with Karl Friston, 2020, to gain insight into the intricacies of the free energy principle: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TcFLQvz5uEg.

Other excellent introductive videos are:

“How the brain shapes reality”, by Andy Clark, 2024

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A1Ghrd7NBtk

“How Free Energy Shapes the Future of AI”, by Karl Friston, 2023

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hHsuOc3240k

The Free Energy Principle

The Free Energy Principle is a theory developed primarily by Karl Friston in the early 2000s. Friston posits that the brain, like all living systems, functions by minimizing its free energy, a measure of surprise or uncertainty, constantly seeking to balance its understanding of the environment with its ability to adapt to new information. By minimizing their free energy, biological systems strive to reduce the discrepancy between their predictions and actual sensory inputs. They can thus maintain a state of balance and avoid unforeseen situations, by making their model of the world as accurate as possible, reducing surprise and constantly adapting to their environment.

Predictive Coding and active inference are candidate computational accounts consistent with the Free Energy Principle, generating predictions about upcoming sensory inputs. These predictions are then compared to current sensory inputs and discrepancies between the predictions and reality, “prediction errors,” are transmitted through the neural hierarchy to refine the brain’s internal models, thereby improving future predictions. These different concepts offer an integrated vision of how the brain processes information and interacts with its environment, minimizing surprise, in other words, optimizing the model’s fit to the data.

From a technical point of view, Friston’s theory involves a quantity called the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, a type of loss function used in Bayesian inference to measure the gap between two probability distributions — for example, between a system’s current beliefs and its prior expectations. It is sometimes called information gain or Bayesian surprise. Mathematically, it can be written as KL(P‖Q) = ∑ᵢ P(i) log (P(i)/Q(i)), where P represents the posterior distribution (updated beliefs given data) and Q the prior distribution (beliefs before data). If the two distributions are identical, the KL divergence is zero — there is no surprise. The larger the divergence, the greater the mismatch between prediction and reality. In Friston’s account, minimizing variational free energy (which upper-bounds surprise) provides a mathematical description of how the brain may reduce prediction error and keep its internal model aligned with the world. Equivalently, active inference treats both action and perception as processes that minimize this same bound on model evidence.

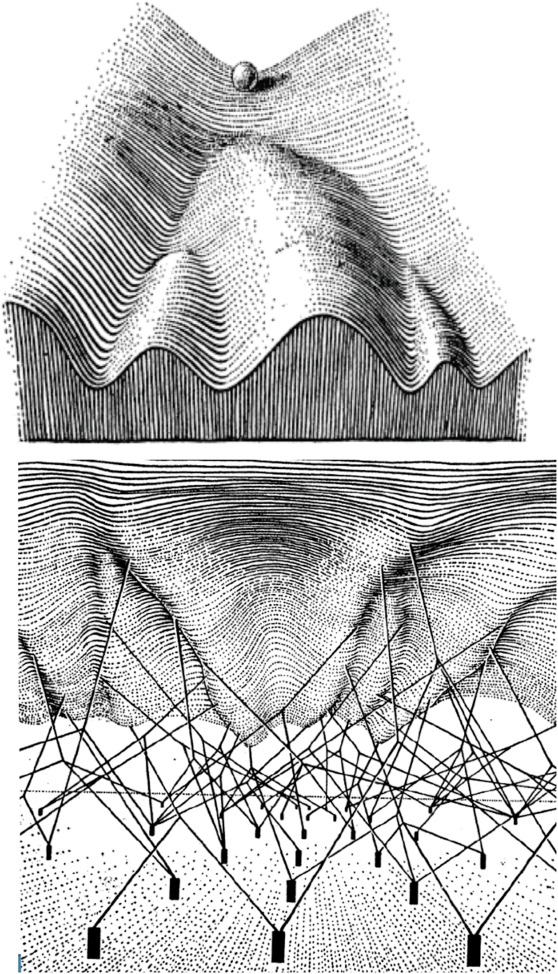

It is above all the notion of “Free Energy Landscape” that determined the direction that the project took, following in particular discussions with the psychiatrist Michael Koslowski, also a resident at Imera and with whom I started a collaboration. In the context of the brain, these Free Energy Landscapes can be thought of as topographical maps where valleys represent low free energy states and peaks represent high free energy states. In a valley, the surprise is minimal, in other words, the system model is in good agreement with the observed data. By seeking to minimize its free energy, that is, by constantly adjusting predictions based on errors, the state of the brain shifts towards the valleys of this landscape. The Free Energy Landscapes thus provide a visual perspective on this process, showing how the brain moves towards states of lower uncertainty.

Left: Conrad Hal Waddington’s Epigenetic Landscape (1957), ancestor of the Free Energy Landscapes

The genesis of the aforementioned ideas can be traced back to the personality of the physiologist and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, one of the fathers of thermodynamics and the inventor of the notion of free energy. In 1867, he proposed the concept of “unconscious inference“. Helmholtz was one of Freud’s idols in his youth (see his letter to Martha Bernays on October 28, 1883). The history of psychoanalysis is the story of its emancipation from scientism and Helmholtz’s foundational ideas in physiology, which were actually forgotten for nearly a century. These ideas have resurfaced in the context of the discoveries in Artificial Intelligence (cf. The Helmholtz Machine, by Geoffrey E. Hinton et al., 1995). Karl Friston has recently drawn many parallels between the Free Energy Principle and psychoanalysis, notably with Freud’s “principle of pleasure”. Other thinkers also attempt to combine neuroscience and Freudian theory, such as Mark Solms, for whom the limbic system could be responsible for some of the phenomena described by psychoanalysis, such as emotions, dreams, or desires. These bridges are an active and sometimes contentious area; I present them here as suggestive avenues rather than established consensus.

The brain’s cognitive functions give rise to a variety of phenomena, ranging from basic neuronal activity to vivid images and language structures. These different forms of representation coexist and interact in complex ways. In the context of dreams, Freud distinguished between manifest and latent content. The manifest content is the literal content, storyline, and images of the dream as the dreamer remembers and recounts it. According to Freud, the manifest content is the disguised version of the underlying thoughts and desires of the dreamer, transformed by the dream work into a less threatening form to ensure the dreamer’s sleep is not disturbed. The latent content refers to the hidden, unconscious wishes, thoughts, and desires that Freud believed were the true meaning of the dream. The latent content is revealed through the process of dream analysis and interpretation. It represents the underlying symbolism of the dream’s manifest content and is thought to be censored and distorted by the dreamer’s mind to protect them from distress or social taboos. He compared the structure of dreams to a rebus, but unlike a traditional rebus, the language of dreams is not reduced to a fixed set of images linked to sounds. Instead, dream images interact according to plastic and emergent rules.

It is tempting to imagine that the topography of an unconscious “structured like a language” is a projection, a shadow, of a larger and less normative landscape, anomic and imaged raw material of the unconscious. The “effective landscape” of associations of ideas of Dreamlogs would then appear as a superstructure emerging above the foundations constituted by the Free Energy Landscapes of neuroscience. In this landscape, a low free energy state would indicate a situation where the brain’s predictions about language are in agreement with what is actually heard or read. Here’s how it might manifest in the everyday use of language: If you listen to someone speak in a familiar context, your brain is constantly making predictions about what words and sentences will follow. For example, if someone says “I’m going to grab my…”, you might anticipate words like “coat”, “bag” or “umbrella”, especially if you’re near a door or if it’s raining out. If the person completes the sentence with “umbrella,” then your prediction was correct, and you are in a state of low free energy. In this case, comprehension is generally easier and smoother, as we often find it easier to understand speech or texts in familiar contexts or on topics that we know well. If, on the other hand, the person completes the sentence with something unexpected, like “I’m going to take my elephant,” it creates a surprise. Your brain then recognizes a gap between prediction and reality, which corresponds to a state of higher free energy. It could then adjust its internal models to take this new information into account.

If information is lost during the transition from neuronal activity to pictorial representations, then to language structures, it is nevertheless possible that the analysis of these language structures offers us clues about the underlying processes, which remain inaccessible to shared experience. Designing a complete correspondence model, which would bring us closer to a deep understanding of the geometry of idea associations, and potentially of the unconscious itself, represents a major challenge. The associations of ideas could follow physical laws to be identified; streams tumbling down winding slopes, would make their way through a constantly evolving landscape, shaped by the forces of desires and impulses. It will be necessary to understand the importance of local minima, the changing of the point of view, the probabilistic nature and complexity of the processes, the volatility of the landscape, and also how to consider possible anomalies linked to slips of the tongue and other linguistic phenomena, in short the whole psychopathology of language manifestations. The continuation of this attempt at theorizing will require much further investigation.

“. . . the activity of the first psi-system is directed toward securing the free discharge of the quantities of excitation, while the second system . . . succeeds in inhibiting this discharge . . .”

Sigmund Freud, Die Traumdeutung

The Unconscious is structured like a Large Language Model

The Unconscious is structured like a Free Energy Landscape

The Unconscious is structured like a GPS for Uberweed

The Unconscious is structured like a Topos

Christophe Bruno, 2023, Dreamlogs

Some avenues to explore

The Landscape of Complex Networks

The article “The Landscape of Complex Networks” by Weinan E, Jianfeng Lu et Yuan Yao deals with the study of complex networks using a combination of advanced mathematical tools and concepts from theoretical physics. The authors use persistent homology, a central technique of Topological Data Analysis (TDA), to study the topology of a dataset across different scales. This method, which the authors applied to Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables, is particularly effective at identifying structures that persist across different resolutions, thus offering an approach that could lead to the determination of Free Energy Landscapes for a complex semantic network.

From texts to landscapes

André Ourednik is a geographer and writer. There are very interesting pages on his blog on the question of transforming texts into landscapes. Ourednik presents a three-dimensional landscape which visualizes the relationships between different words, in a corpus made up of three texts by the French anarchist writer and geographer Élisée Reclus: Histoire d’une Montagne, Histoire d’un ruisseau and L’Anarchie. The resulting map is based on a technique called principal component analysis (PCA), which makes it possible to simplify complex data by representing it in a reduced-dimensional space, while retaining as much relevant information as possible. In the resulting 3D maps, words that have similar meanings or contexts are grouped together and appear close to each other. On the other hand, words that are very different from each other are far apart on the map.

Alluvial diagrams

Alluvial diagrams provide an intuitive and visual way to understand complex relationships and data flows, and are useful for exploring citation networks and dynamics in academic research. They offer an interesting perspective on semantic dynamics, word associations and recurring patterns in dreams and language. They could help visualize unexpected associations or recurring themes. Algorithmically analyzing word associations on the Internet, it would be possible to use these diagrams to visualize semantic clusters and trends in word usage. By zooming out, alluvial diagrams could visualize how these interconnections evolve and influence culture at different times. By combining the fine granularity of word associations with a broader perspective on cultural movements, alluvial diagrams would provide an overview of cultural dynamics through time, offering a deeper understanding of semantic and historical interconnections, and making these visually accessible relationships.

From the unconscious as topos to the unconscious as landscape

The book À l’ombre de Grothendieck et de Lacan, Un topos sur l’inconscient, written in 2022 by the mathematician Alain Connes and the psychoanalyst Patrick Gauthier-Lafaye, explores the link between the concept of topos, one of the peaks of contemporary mathematical thought introduced by Alexandre Grothendieck, and the notion of the unconscious developed by the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.

Toposes are a generalization of the notion of topological space. They allow working in contexts where classical logic does not directly apply, providing flexibility for studying complex mathematical structures. The book proposes that the concept of topos, deus ex machina where apparently incompatible truths can coexist, can be identified with the structure of the Lacanian unconscious, a sort of backstage where different signifying chains, representations and desires can interact. The authors, overcoming an academic taboo nearly twenty-five years old (see e.g. the Sokal affair), do not hesitate to assert on page 26, in a flourish worthy of the finest postmodernist paradoxes, that “the unconscious is structured like a topos”.

Being only vaguely familiar with topos, I will base myself on the comments of the mathematician Lieven Le Bruyn who, on his blog, makes the link between the book by Connes and Gauthier-Lafaye, and a recent article co-written by Tai-Danae Bradley, a mathematician known for her work at the intersections of mathematics (including topology and category theory) and AI. In this article, the authors consider the set of all possible texts written in a given language; it can also be a set of web pages, used to train an LLM, or even a set of someone’s memories. Cut these texts into pieces, and link each of them to all the pieces of text obtained by deleting a few words at the beginning and/or at the end of it. For example, the phrase “a red rose” will point to “a red”, “red rose”, “a”, “red” and “rose”, but not “a rose”.

You thus construct a category in the mathematical sense: that of partially ordered sets (or poset). The minimal elements are the individual words, the maximal elements are the texts or websites from which we started. Considering all initial (i.e., maximal) texts which contain a given expression like “a red rose”, one obtains what is called the presheaf associated with “a red rose”.

© neverendingbooks

The topos of presheaves is then the category of all presheaves on this poset (viewed as a category). In other words, it is the set of all possible presheaves on the poset made up of fragments of texts. In the topos of presheaves, each presheaf becomes a particular object, and these objects are connected by morphisms (or arrows), which respect the categorical structure of the presheaves. This is similar to the notion of semantic neighborhood on Google (search engines, however, use other algorithms to classify and display results, such as relevance, site popularity, inbound links, etc.). The topos of presheaves, in the context of Dreamlogs, corresponds, roughly, to all the possible results that Google returns for a given phrase (their semantic neighborhood), this for all the possible phrases of the language. If two fragments appear together in the same context, this can be interpreted as an association of ideas, represented by a morphism between the presheaves associated with these phrases.

In summary, in the topos of presheaves, the objects are presheaves (which represent fragments of text and their contexts) and the morphisms between these objects represent the associations of ideas or relationships between these fragments.

As I write these lines, I am reminded of this remark by Jean-Yves Girard on “the essentialism inherent to the categories: from which Heaven did this form fall that morphisms so respectfully preserve?” In any case, Dreamlogs can be read as approaching a linguistic topos, with associative paths acting like morphisms between presheaves—an interpretive lens rather than a literal identification. Maybe this gestures toward the topos of the unconscious that Alain Connes and Patrick Gauthier-Lafaye imagine, or toward what Lacan intuited in his late turn to topology. This remains an exploratory analogy. While Connes & Gauthier-Lafaye develop a bold mathematical-psychoanalytic identification, my use of topos-theoretic language here is heuristic: a way to structure intuitions about language and association of ideas, not a claim of formal equivalence.

Phylomemy

Phylomemetics (or phylomemy) could constitute an alternative method to progress in my research topic. It is a branch of memetics that studies the evolution of memes over time analogous to the way phylogeny studies the evolution of biological species. It attempts to map and analyze the evolutionary tree of memes, identifying their origins, their branches, and how they evolved or adapted to different cultural environments. The concept is based on the idea that memes, like genes, undergo a process of selection, mutation, and adaptation within the cultural landscape. On this subject, one can consult the works of David Chavalarias and Quentin Lobbé, as well as those on phylomythology, a recently developed method of analyzing mythologies.

Remarks

Universality

My residency provided an opportunity to go deeper into the concept of a Free Energy Landscape and its universality. This representation is a staple in statistical physics and quantum field theory, often associated with second-order phase transitions and spontaneous symmetry breaking. Since the 1930s, similar ideas have appeared in various fields. A non-exhaustive list includes biology, genetics, epidemiology, oncology, neuroscience, the modern theory of memory (as explored by Hebb, Little, Hopfield, Amit, and others), protein folding, socio-ecological systems, the theory of panarchy, economics, finance, management theory, complex networks, catastrophe theory, spectral theory for graphs and Hodge Laplacians, Topological Data Analysis, Morse theory, persistent homology, community detection, homologies and templates for chaotic attractors, spin glasses, memetic algorithms, and deep neural networks… Depending on the discipline, Free Energy Landscape are termed as “adaptive landscape,” “fitness landscape,” “attractor landscape,” “search landscape,” “epigenetic landscape,” “phenotype landscape,” “loss landscape,” “error landscape,” or even the “string theory landscape.” Notable references in this context are Wright (1932), Waddington (1939), Thom (1968), Kauffman (1987), and of course, Karl Friston.

Negative results

In Dreamlogs, the hypergraph of language is envisioned as the informational cloud of a hypothetical subject — a repository for all of humanity’s words. The informational processes occurring during its virtual lifespan, from its fictional birth to an equally fictional death, are posited to be equivalent to the set of all the informational processes on the Web, which I sometimes facetiously (sometimes not so facetiously) equate to the “unconscious of Big Tech”, or to the “unconscious of Capitalism.” This assumed “ergodicity” allows us to sidestep the concept of a collective unconscious and focus on the subject of language, even if it’s retrospectively pieced together and isn’t bound to a single conversational partner. Nonetheless, the dilemma of non-ergodicity lingers. Navigating an “associative landscape of ideas” as suggested by Dreamlogs is an overwhelming optimization task, making it impossible to explore every potential trajectory.

This negative result, linked to non-ergodicity, echoes an article by Cristian Calude and Giuseppe Longo dating from 2016. In “The Deluge of Spurious Correlations in Big Data”, they demonstrate that very large databases necessarily contain arbitrary, fallacious and therefore unusable correlations, which only appear because of the size, and not the nature of these data. Even assuming perfect transparency and total visibility of behavioral data, predictability is not proportional to the abundance of this data. Too much information kills information.

If we find ourselves entangled in a conceptual maze, these reflections have helped me in navigating between the psychoanalytic perspective, according to which the subject is in no way a circumscribed individual – on the contrary, it is divided, ineffable, radically non-ergodic -, and the intricacies of complexity theory, which we will now dive into.

Rorschach inkblot test

imgur.com/t/knowledge/6K8GvyO

Our brain balances between aesthetics and politics.

Complex systems

Guided as much by physicist Philip W. Anderson’s “more is different” quote as by Marx and Engels’ analysis of the transition from quantity to quality, Dreamlogs has turned to non-reductionist theories of complexity, while maintaining a critical stance toward big data. Among the tools of theoretical physics, the theory of renormalization is used to analyze the shift from one scale to another, an essential property for examining phase transitions, in particular between an ordered phase and a disordered phase. These transitions between different states are often accompanied by spontaneous breaking of symmetries. At the heart of these transitions is the notion of a “critical point.” At this point, the correlation lengths become infinite, thus eliminating any characteristic scale of the system. The medium is then dominated by collective effects which lead the thermodynamic quantities to follow power laws. These laws, atypical because they are non-Gaussian, are the distinctive sign of complex systems approaching or oscillating around a critical point, as in the transition from paramagnetism to ferromagnetism.

An enlightening example is provided by the Bianconi–Barabási model. It describes a topological phase transition between a “rich-get-richer” phase also known as “preferential attachment”, and a condensation (“winner-takes-all”) phase where a few super-hubs dominate, attracting almost all the links. The associated energy landscapes are expected to reflect these transition dynamics and incorporate fractal characteristics that arise from these scale invariance phenomena.

The Dadameter for example has a hierarchy of scales which is broken down into three levels:

- Microscopic: At the finest scale, we find the nodes that represent words, and their local interactions, shaped by associations of ideas.

- Mesoscopic: progressing towards a larger scale, we encounter the journeys of speaking beings and the discursive cloud that surrounds them, thus revealing their interactions and dynamics within the system.

- Macroscopic: at the broadest level, the Dadameter captures cultural and artistic movements that are shaped by lower scales and shapes them in return.

In the “macroscopic” context of political economy, if an “authoritarian” phase of the “winner-takes-all” type followed a “liberal” phase of the “rich-get-richer” type, such a transition could be reflected in individual “microscopic” trajectories across the landscape of Dreamlogs, oscillating between anomic primary processes and normative secondary processes.

If we could apply the theory of renormalization to these data at the “microscopic” scale, it would be possible to reconstruct, in bottom-up mode, individual agents at the “mesoscopic” scale. We could then infer major historical movements on a “macroscopic” scale. Such an approach would have profound implications for diverse fields, from the history of art to the history of science to political economy.

In the framework of complex systems theory, the hypergraph of language, assumed to be always evolving and out of equilibrium, can be compared to emergent phenomena such as the coordinated movements of swarms of birds, which self-organize without necessarily being influenced from the outside. We can also make a comparison with financial markets where flows of information, similar to associations of ideas, circulate. These flows can cause abrupt fluctuations due to feedback loops. The latter, stimulated by incessant interactions, have the potential to stabilize or destabilize the system. In the same way that a market can be disrupted by unexpected news, the hypergraph of language is sensitive to cultural events and news, which can alter its structure. These influences can be interpreted as “perceptions” or “drives,” to the extent that the “id,” the source of the drives, is seen as an external force.

In this system, trajectories can vary unpredictably, reminiscent of chaotic dynamics. Notions such as feedback loops, self-organized criticality, edge-of-chaos behavior—concepts notably explored by Stuart Kauffman—and the criticality hypothesis are often invoked in discussions of complex adaptive systems; I refer to them here as organizing intuitions rather than as fitted models for Dreamlogs. Non-ergodic systems such as spin glasses exhibit rugged energy landscapes with many local minima, making exploration arduous. Yet such complexity can be advantageous, as in certain theories of memory where the roughness of the landscape is proportional to storage capacity.

There is a deep connection between energy landscapes, the attractors of a complex system and their bifurcations, and theories like catastrophe theory. The study of entropic cycles around critical points (“at the edge of instability”), combined with recent ideas on chaos control, opens up intriguing research possibilities. One could for instance imagine thought experiments involving some heat death of the universe of discourse.

Finally, alongside complexity theory, socio-ecological systems theory offers a unifying perspective on the dynamics of complex ecosystems. At the heart of this theory is the concept of “panarchy”, which describes how these ecosystems evolve through adaptive cycles over overlapping time scales:

- Emergence (reorganization): new structures begin to form.

- Expansion (exploration): phase of rapid growth and exploration.

- Stabilization (conservation): the system becomes more stable and less flexible.

- Collapse (release): period of rapid disruption, then release of resources.

These ideas, whose origins date back to the 1970s, generalize the basic examples of Lotka-Volterra predation cycles or Kondratiev cycles in economics.

To be continued…

Appendix 1: past exhibitions, articles and credits

The project Dreamlogs received support from DICRéAM (CNC Ministry of Culture and Communication, assistance à la maquette), in 2004. The first version was coded by Sylvie Tissot. A second version was developed by students of ESIEA engineering school in Paris, thanks to the help of Claire Leroux, founder of ARNUM Lab.

It was notably exhibited at the Read_Me 2004 Software Art Festival (Aarhus, Denmark – curated by A. Shulgin, O. Goriunova, S. Pold & al.), at the Nuit Blanche in Paris (October 2, 2004, Mairie du 4ème), at the Sollertis Gallery (Toulouse, 2005); it has also been the subject of numerous presentations by me at conferences, workshops, or in articles I have written for various journals.

Two articles, one by Etienne Candel (PhD & HDR, Professor at the University of Paris), and the other by Søren Pold (PhD, Associate Professor and Researcher in Digital Aesthetics, Aarhus University), provide complementary insights into my work:

Miracles et mirages de l’autoédition : la « défiguration » comme critique formelle et comme détournement – Le cas des Dreamlogs de Christophe Bruno, Étienne Candel, Réseaux 2006/3 (no. 137), pages 69 à 95

“The author proposes to highlight in this article the notion of defiguration, a process by which a network text is transformed in its layout, formatting, and its own editorial characteristics, that is to say, in what is commonly called, with Yves Jeanneret, its textualization. The notion of defiguration emphasizes the semiotic impact of editorial enunciation on the Internet. The work studied here, Christophe Bruno’s Dreamlogs, diverts a canonical form of a blog into a deviant practice of self-publishing. It manipulates the cognitive routines of the Internet user and, by defiguring the texts, it questions common practices of writing, reading, and interpretation.“

Literature from Page to Interface: The Treatments of Text in Christophe Bruno’s Iterature, Søren Bro Pold, 10-11-2007, Electronic Book Review, 10-11-2007

“Søren Pold explores the ways in which Christophe Bruno’s Iterature expands the notion of literary form and shows what happens when words are no longer only part of a language.“

Also of interest concerning Dreamlogs:

Hacking Google / Against Algorithmic Governmentality, Jean-Paul Fourmentraux, Revue 02, (n° 137, summer 2021), pages 33 to 37

antiDATA – La désobéissance numérique – Art et hacktivisme technocritique, Jean-Paul Fourmentraux, Les presses du réel, Nov. 2020

“A doctor in theoretical physics, converted to art in the early 2000s, the French artist Christophe Bruno conceived his work as a true Trojan horse against the hegemony of Google. In 2001, he embarked on a systematic enterprise of critical and prospective hijacking, often whimsical, of the features and uses of the now famous and ‘essential’ search engine.“

Comment hacker les Gafam à l’ère de la post-vérité ?, Christian Salmon, Slate.fr, 2022

“In residence for a year at the Institute for Advanced Studies of Aix-Marseille University, Christophe Bruno has expanded the scope of his web navigation to include the realms of the unconscious and dreams. His digital creations offer a different way to browse the internet. They take improbable trajectories in the space of discourse, previously unknown paths, wandering paths, and allow us to visualize the contours of this “open sky unconscious,” the unconscious of Big Tech in the era of “post-truth.” ‘It’s a bit,‘ comments the artist, ‘as if Edward Bernays, Freud’s nephew, came back to our mad world to update his book Propaganda.'”

Appendix 2: Dreamlogs and Oulipo

Dreamlogs is similar to certain works of Oulipo (which themselves draw a lot of inspiration from Raymond Roussel), in particular to the “Dossier P.A.L.F., Production Automatisée de Littérature Française, Presbytère et prolétaires” by Marcel Bénabou and Georges Perec, who spent several years, between 1966 and 1973, cutting up the Littré dictionary with scissors, anticipating the generalization of “cut and paste” in the digital world. The idea of the P.A.L.F. project is as follows: take a text or a sentence and replace each word with its definition in the dictionary. Then repeat the process and observe how the text evolves. Then take another text, as different as possible from the first, and do the same. After a series of iterations, the two must converge into a single, immense intermediate text. In the P.A.L.F., the source was “Le presbytère n’a rien perdu de son charme ni le jardin de son éclat.“, and the goal, “Prolétaires de tous les pays, unissez-vous !“. Which would give in terms of graphs:

Instead of using dictionary definitions, Dreamlogs use the concept of proximity of two elements of discourse in terms of lexical collocation on the Web: two phrases are linked together if they appear together on the same Web page, and they will be all the closer the more they are found in a large number of pages. By following the paths in the graph (more precisely, the hypergraph), we generate Dreamlogs. An elementary vertex looks like this:

We can thus see the Dreamlogs as a generalization of the P.A.L.F. in the era of the World Wide Web, obtained by relaxing Oulipian constraints. Like Dali’s soft watches, Dreamlogs bathe in a more flabby universe, with more general laws of invariance and symmetry (in a way, they are to the P.A.L.F. what general relativity is to special relativity, or what topological field theories are to general relativity). In 2006, I had the chance to discuss with Marcel Bénabou, as well as Paul Braffort and members of the Collège de Pataphysique, who confirmed to me the relationship of the two projects. For my part, I also imagined my device as a means of addressing the question of the association of ideas, of dreams, and of Freud’s “primary processes”. The latter correspond to transverse, associative navigation, typical of “geodesic” trajectories of Dreamlogs, while the “secondary processes” correspond to the utilitarian narrative order, that which is usually found within a text written by a person according to a functional, so-called “rational” objective. The first process is vernacular, liberal, spontaneous and anomic, the second, vehicular, constraining, reflective and normative.

Here are some extracts from the Dreamlogs documentation in 2003:

“Dreamlogs are an engine for associations of ideas. They offer another way to navigate the Internet, untangling the thread of discourse that has become tangled over time. They constitute a new interface to Global Text: a non-utilitarian and non-local alternative to Google. Dreamlogs confront the temporality of a dreamed life with the indefinite dimensionality of speech.“

“Choose a word or part of a sentence as a starting point: “I love life,” “I’m sad,” etc. what you want. When you press “Go”, the program searches for related text fragments among all texts containing the entry. Then choose another word or another phrase from the texts displayed by clicking on it, and repeat the process. At the end, save your journey and you will see the generated Dreamlog. The initial idea of the project was to obtain the longest and most “non-local” paths possible. Otherwise, you can just wander around the space of discourse.“

“Dreamlogs produce streams of associations of ideas on the Web. Starting from one discursive position, you can for example try to reach the opposite position in a finite number of steps. To do this, you start from a discursive position, and little by little, through associations of ideas, you move away from your initial position; in the end you eventually find yourself in opposition to who you were in the past, a bit like in real life we abandon our childish utopias as we grow up. From this final position, you have enough perspective to see the entire path traveled from another perspective, and to be able to see yourself as you were, through a sort of “global mirror‘.”

Appendix 3: Simulation of Dreamlogs by ChatGPT

I transcribe below the conversation with ChatGPT-4 where the AI simulates the associative process of Dreamlogs (it can also perform these simulations by accessing the Internet in real time). This experiment provides an interesting direction to pursue in the perspective of reactivating the project, although it is difficult to verify the validity of the AI’s responses (which cannot access its internal embeddings explicitly). Search-engine indices and page counts are volatile, so trajectories are only weakly reproducible over time. This experiment was conducted multiple times during my residency, but the one transcribed below is from October 4, 2023.

CB: In his Dreamlogs project, Christophe Bruno offers navigation in what he calls the hypergraph of language. Here is the principle of the system: the user chooses one or more words, for example: “I love life”, “I am sad”, etc. whatever comes to mind, in any language… then click “Go”. The computer program then launches a search on Google and retrieves the corresponding pages via their ‘Cached’ snapshots, extracting sentence fragments from all texts containing the input (i.e., belonging to its semantic neighborhood). These snippets are then displayed in the interface and transformed into hypertext. The user can then select new phrases from the proposed results in just a few clicks. These become the starting point for new research and the process can continue in this way endlessly. Your LLM is based on this type of semantic proximity and word embeddings. You can also adjust a temperature parameter: a high temperature corresponds to low correlations between phrases and vice versa. Could you simulate a “navigation” of the type offered by Dreamlogs? You would have to start from a sentence and associate it with another neighboring sentence (use short sentences, of 5 words on average). Give two examples with 10 steps each. The first at low temperature and the second at high temperature.

ChatGPT: Of course, I can simulate navigation based on semantic proximity, similar to that offered by Dreamlogs. Here’s how I’m going to do it:

- For low temperature, I will choose sentences that are very close semantically to the previous sentence.

- For high temperatures, I’m going to choose sentences that may be a little further away semantically from the previous sentence.

Low temperature navigation:

- I love life.

- Life is beautiful.

- Beauty is everywhere.

- There is hope everywhere.

- Hope keeps us moving forward.

- Moving forward is essential.

- What is essential is invisible to the eye.

- The eyes are the mirror of the soul.

- The soul is eternal.

- Eternity is a mystery.

Navigation at high temperature:

- I love life.

- The apples are red.

- Red is a warm color.

- The hot chocolate is delicious.

- Delights come from the heart.

- The heart has its reasons.

- The reason is sometimes misleading.

- Illusions can be fun.

- The funfairs are noisy.

- The sound of the sea is calming.

These navigations are simulations based on semantic proximity and may vary depending on the parameters and models used.

CB: Thank you, can you tell me numerically what temperatures you used?

ChatGPT: I used a conceptual approach to illustrate the difference between low temperature and high temperature. In language models like mine, “temperature” is a parameter that influences the diversity of responses. A lower temperature makes the model more deterministic, while a higher temperature makes it more random.

For the examples I gave:

- For low temperature navigation, I conceptualized a temperature of around 0.2.

- For high temperature navigation, I conceptualized a temperature of around 0.8.

These values are indicative and serve to illustrate the difference in behavior of the model at different temperatures. In a real-world application, you could adjust the temperature to achieve the desired level of diversity in the responses.

CB: What is the maximum temperature of your LLM?

ChatGPT: Temperature in a language model like mine is a parameter that can theoretically take any positive value. However, in practice, commonly used values are generally between 0 and 2.

- A temperature of 0 makes the model completely deterministic, always choosing the most likely output.

- A temperature of 1 uses the model probabilities as is.

- A temperature above 1 increases the randomness and diversity of outputs, making the model more creative but also potentially less coherent.

There is no fixed “maximum temperature” for the model, but as the temperature increases, the responses become more and more random and may lose relevance.

CB: Give me two new examples over 10 steps, the first at zero temperature if possible (or very close to 0) and the second at high temperature, much higher than 2 if possible.

ChatGPT: Okay, I’m going to simulate navigation based on semantic proximity with these extreme temperatures.

Navigation at very low temperature (close to 0): When the temperature is very low, the model tends to be very deterministic and to choose sentences very close semantically to the previous one.

- Life is precious.

- Life is beautiful.

- Life is a gift.

- Life is an adventure.

- Life is full of surprises.

- Life is full of challenges.

- Life is full of opportunities.

- Life is full of moments.

- Life is full of emotions.

- Life is full of joy.

Browsing at very high temperature (above 2): With very high temperature, sentences may seem random and less semantically related.

- Life is precious.

- Frogs like to jump.

- The sky was dotted with stars.

- Socks always disappear.

- The mountains touch the clouds.

- The chocolate melts in the sun.

- Dreams are made of cotton.

- Trees talk to birds.

- Shoes tell stories.

- The moon dances with the waves.

These navigations are simulations based on semantic proximity at different temperatures and may vary depending on the parameters and models used.

CB: How hot is this last example?

ChatGPT: In the example I gave for very high temperature navigation, I conceptualized a temperature of around 3 to illustrate very random behavior of the model. This is an indicative value to show how the model might behave with elevated temperature, producing more diverse and less predictable responses.

CB: We are going to do a new exercise. Set yourself to a slightly lower temperature than in your last example, perhaps 2 instead of 3, so that the semantic correlations remain somewhat visible although very tenuous. Forget the limitation on the number of steps. It will now be a matter of starting from a first sentence and arriving at a final sentence which has a completely opposite meaning to the first (for example here, this final sentence could be “my life is worthless”).

ChatGPT: Okay, I’m going to simulate navigation based on semantic proximity with a temperature of 2 to get more random transitions while maintaining some semantic correlation. I’m going to start from the phrase “Life is precious” and try to get to “My life is worthless”.

- Life is precious.

- Every day brings new opportunities.

- Dawn is the most peaceful time.

- The sea sparkles under the rising sun.

- The waves evoke distant memories.

- Memories can sometimes be deceiving.

- Reality is often more complex than we think.

- Challenges shape and define us.

- Loneliness can be overwhelming.

- The dark nights seem endless.

- Hope is sometimes hard to find.

- Sadness can invade our hearts.

- Every tear tells a story.

- The sad stories are often the most touching.

- Pain is a powerful emotion.

- Feeling lost is natural.

- My life is worthless.

CB: Now increase the temperature to 3.

ChatGPT: Okay, with a temperature of 3, the transitions will be more random. Here is a new navigation based on this high temperature:

- Life is precious.

- The stars shine at night.

- Cats like to chase birds.

- Music soothes the soul.

- The mountains touch the sky.

- Chocolate is comfort.

- Dreams are made of clouds.

- The trees whisper secrets.

- The rain dances on the roofs.

- Books open doors to other worlds.

- Imaginary worlds are endless.

- The end of one story is the beginning of another.

- Beginnings are always exciting.

- Excitement can sometimes lead to disappointment.

- Disappointment is a part of life.

- Life has its ups and downs.

- Sometimes I feel insignificant.

- Insignificance can lead to feelings of hopelessness.

- Despair is a dark valley.

- My life is worthless.

With a high temperature, the transitions are more random, but I tried to maintain a certain semantic fluidity.

CB: Can you do the exercise again by browsing the Internet in real time, to be closer to the idea of the Dreamlogs? This will probably take longer but let’s try.

ChatGPT: Of course, here is a series of sentences based on real-time Internet searches, inspired by the idea of Dreamlogs:

- Life is precious. Source

- Every moment we have on this earth is unique. Source

- Every moment offers an opportunity to create memories. Source

- It is important to seize these opportunities and live them to the fullest. Source

- Don’t be afraid to step out of your comfort zone. Source

- Get out there and explore new horizons. Source

- What topics interest you? Source

- Technology and science. Source

- Improving our quality of life. Source

- Setting goals is essential to success.Source

CB: Now, without navigating in real time, let’s do another exercise. Forget the constraint on the number of words in a sentence, they can be longer. You must start from the sentence “The presbytery has lost none of its charm nor the garden of its splendor. » and arrive at “Proletarians of all countries, unite!” “. There is no a priori limit on the number of steps. Set yourself to a temperature of 2.

You must also take into account the following two constraints: 1) two consecutive sentences must not contain the same word (or two etymologically close words – 2) sentences in the same sequence must have varied syntactic structures.

ChatGPT: Okay, with a temperature of 2, here is a semantic navigation between the two sentences:

- The presbytery has lost none of its charm nor the garden of its splendor.

- In the darkness, the stars twinkle.

- Who knows what tomorrow will bring?

- The majestic mountains defy the sky.

- The water of the rivers whispers ancient secrets.

- Beneath the burning sand, the deserts hide mysteries.

- The oceans embrace the shores, eternally.

- In the forest, every creature has a story to tell.

- The seasons pass, leaving their mark on the world.

- Over time, civilizations rise and fall.

- Why do philosophers constantly question the universe?

- Art, in all its splendor, captures the human soul.

- Revolutions, although tumultuous, shape the future.

- Listen ! Voices are raised, calling for fraternity.

- In a constantly changing world, unity is our strength.

- Proletarians of all countries, unite!

« On trouve en effet, dans l’Interprétation des rêves de Freud, de quoi nourrir une assez intéressante comparaison. Car le traitement que le P.A.L.F. fait subir à l’énoncé initial ressemble étrangement à celui que le rêve fait subir aux pensées du rêve, « fragments tordus, morcelés, réunis comme des glaces flottantes » : « le rêve, dit Freud, laisse là toutes les conjonctions et ne travaille que sur le contenu effectif des pensées du rêve » (éd. Gallimard, p. 269).

Ainsi liée au travail du rêve, la méthode ne me paraît que mieux à même d’être au centre de la démarche poétique. Car enfin, qu’est-ce que le P.A.L.F., sinon la façon aujourd’hui la plus simple, et la moins dangereuse, de pratiquer un exercice devenu aussi inséparable de la condition du poète « moderne » que le manteau et le bâton de celle du philosophe antique : « le dérèglement systématique de tous les sens »?” » Marcel Bénabou, Le dossier P.A.L.F.”

“Indeed, in Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, we find material for an interesting comparison. The way the P.A.L.F. alters the initial statement is strangely similar to how the dream alters the thoughts of the dream: ‘twisted, fragmented pieces, brought together like floating ice’: ‘the dream, says Freud, leaves behind all conjunctions and works only with the actual content of the thoughts of the dream’ (Gallimard edition, p. 269).

Thus linked to the work of the dream, the method seems to me all the more suited to being at the heart of the poetic approach. After all, what is the P.A.L.F., if not today’s simplest and least dangerous way of practicing an exercise that has become as inseparable from the condition of the ‘modern’ poet as the cloak and staff were from that of the ancient philosopher: ‘the systematic derangement of all the senses’?”” Marcel Bénabou, Le dossier P.A.L.F.”